[Agent Part 5] Dual-Agent Architecture: Anthropic Explains the Internal Engineering Design Behind Why Claude Code Feels So Good

![[Agent Part 5] Dual-Agent Architecture: Anthropic Explains the Internal Engineering Design Behind Why Claude Code Feels So Good [Agent Part 5] Dual-Agent Architecture: Anthropic Explains the Internal Engineering Design Behind Why Claude Code Feels So Good](/assets/images/dual-agent-architecture-logo.png)

Disclaimer: This post is machine-translated from the original Chinese article: https://ai-coding.wiselychen.com/anthropic-dual-agent-architecture/

The original work is written in Chinese; the English version is translated by AI.

Anthropic published an engineering approach for long-running tasks. This isn’t about brute-forcing with a bigger model or a longer context window. It’s about designing an engineered workflow so that even under multi-window conditions where the agent repeatedly “forgets,” it can still push the work forward step by step like a human engineer.

I’ve read some reverse-engineering writeups about Claude Code, and they’re broadly very similar to this architecture. And since the article also mentions this was a joint effort by Anthropic’s RL team and the Claude Code team, we can treat it as a good proxy for Claude Code’s design thinking.

Why does a single agent fail?

I’ve said before: long-running tasks are the holy grail for agents. Long tasks involve dozens to hundreds of features. But the model works with limited context each round, meaning every run is a “memory reset.”

A single agent tends to run into two classes of problems:

Problem 1: It tries to do everything in one go. The model starts coding at large scale until the context runs out, leaving “half code” behind—unfinished, undocumented, untested. When the next round of the agent takes over, it can’t tell what progress was made.

Problem 2: It declares victory too early. It sees some UI or an API and assumes the feature is complete, then ends the task.

The core issue isn’t model capability. It’s the lack of a structured working method that can carry task logic across context resets.

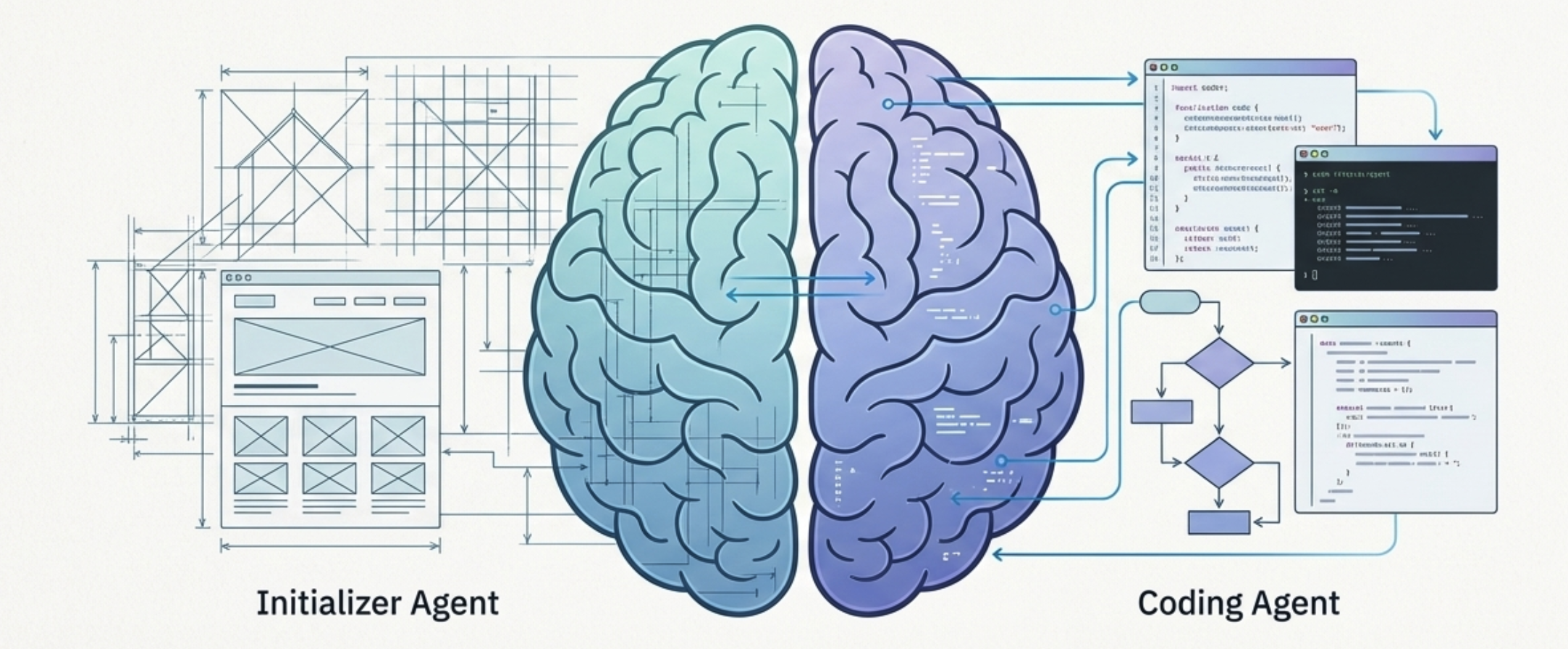

Dual-agent architecture: one directs, one iterates

Anthropic’s solution is to split a long-running task into two roles.

Initializer Agent (principal architect) handles the first run:

- Break requirements into a JSON-structured feature list, each item with acceptance criteria

- Create a

progressfile to record project state, tracked with git - Generate an

init.shbootstrap script to keep the environment healthy

Coding Agent (incremental implementer) handles subsequent iterations:

- At the start of each round, check the directory, read git history, run init.sh, run end-to-end tests

- Pick one unfinished feature from the list—do one thing at a time

- Use Puppeteer to test like a real user; only mark it complete and commit after it passes

This cadence is slower, but extremely reliable. It turns “unattended long-running tasks” into “verifiable dev iterations per round.” It’s very similar to what people describe as Plan, Exec, Critic.

Implementation details: the JSON manifest structure

The feature list uses JSON, and each feature has explicit acceptance steps:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

{

"category": "functional",

"description": "New chat button creates a fresh conversation",

"steps": [

"Navigate to main interface",

"Click the 'New Chat' button",

"Verify a new conversation is created",

"Check that chat area shows welcome state",

"Verify conversation appears in sidebar"

],

"passes": false

}

A critical design choice: the agent may only modify the passes field, and cannot delete or edit the tests themselves. This preserves consistency in acceptance standards.

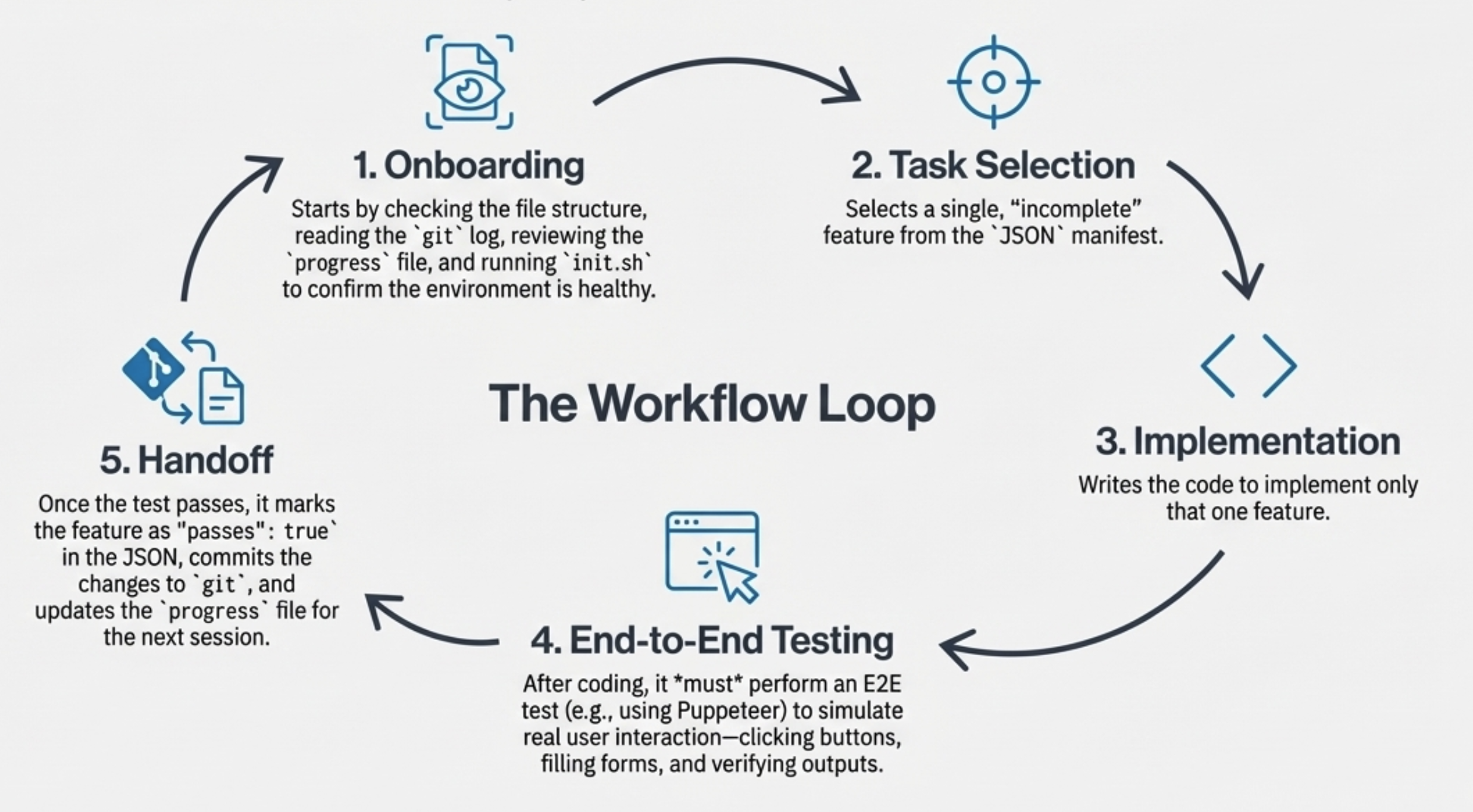

How a Coding Agent session typically starts

Every time a new session begins, the Coding Agent “onboards” itself:

1

2

3

4

[Assistant] 我將開始了解項目當前狀態

[Tool Use] <bash - pwd>

[Tool Use] <read - claude-progress.txt>

[Tool Use] <read - feature_list.json>

That’s why Claude Code often starts by reading CLAUDE.md, checking git logs, and understanding the project structure—it’s rebuilding context.

Common failure modes and how this solves them

Failure 1: The agent declares completion too early → Create a list of 200+ features and force verification one by one

Failure 2: Bugs remain in the environment but aren’t recorded → Force writing to git + a progress file

Failure 3: Features are marked done prematurely → Require self-verification via Puppeteer before marking complete

Failure 4: The agent wastes time figuring out how to start the app → Provide an init.sh script so it’s one command to bootstrap

The article even notes that with the strongest Claude Opus 4.5, “out of the box” still can’t build a production-grade web app across multiple context windows—unless you adopt this structured method.

It’s not the model—it’s the engineering workflow

When I saw this architecture, my first reaction was: isn’t this exactly what SDD has been emphasizing?

- Turn fuzzy requirements into a structured feature list → we call this PRD

- Build state tracking → we use git + progress files

- Ensure every iteration is verifiable → we use QA acceptance workflows

The difference is: humans do it manually; they make the AI do it. But the core insight is the same:

Long-running task success isn’t about how strong the model is, but whether you have a structured workflow that can carry context forward.

Key takeaways

- The bottleneck in long-running tasks is workflow design, not model capability

- Dual agents are “division of labor”: one lays foundations, one iterates

- Structured state recording is the key to cross-session collaboration

- End-to-end testing is required every iteration

- We may soon see Test Agents, QA Agents, Documentation Agents—forming an “AI engineering team”

In the next agent era, the breakthrough may not be bigger models, but a breakthrough in AI agent engineering methodology. That’s also why I’ve been focused on writing technical articles about agent workflows.