OpenClaw, Fully Dissected: Six Layers Every Agent Engineer Should Learn

Disclaimer: This post is machine-translated from the original Chinese article: https://ai-coding.wiselychen.com/openclaw-architecture-deep-dive-what-claude-code-didnt-tell-you/

The original work is written in Chinese; the English version is translated by AI.

Table of contents

- Why dissect OpenClaw’s architecture?

- What exactly is OpenClaw?

- The six-layer architecture: the full path from message to response

- Channel Adapter: unify multiple channels

- Gateway Server: the heart of task orchestration

- Lane Queue: why serialization is the right default

- Agent Runner: dynamically assembling the system prompt

- Agentic Loop: the tool-calling loop

- Response Path: back to you

- Memory system: simple, but effective

- Computer Use: why not screenshots?

- Security design: allowlists and dangerous-command blocking

- Frankly

- FAQ

- Further reading

Why dissect OpenClaw’s architecture?

I recently saw a question on Discord:

“What’s the real difference between OpenClaw and Claude Code? Aren’t they both just LLMs running commands?”

It’s a good question.

On the surface, both are “AI that executes tasks on your computer.” But their underlying architectures are fundamentally different.

Claude Code is a CLI tool—you interact with it by typing in a terminal.

OpenClaw is a gateway server. It can receive messages from Telegram, Discord, Slack, WhatsApp (and more), then execute tasks on your machine.

That difference determines the complexity of the entire system.

In this post I’ll dissect OpenClaw’s architecture end-to-end. Once you understand the pipeline, you’ll know what it’s good at, what it’s not, and why it feels more like an “employee” than Claude Code.

What exactly is OpenClaw?

Here’s the blunt conclusion:

OpenClaw (also known as Clawdbot) is a TypeScript CLI application.

Not Python. Not Next.js. Not a web app.

It’s a process that runs on your local machine and does three things:

- Exposes a gateway server to handle messages from channels (Telegram, WhatsApp, Slack, etc.)

- Calls LLM APIs (Anthropic, OpenAI, or local models)

- Executes tools on your computer, including shell commands, file operations, and browser control

So what’s the biggest difference vs Claude Code?

Claude Code has a single interaction surface (the terminal). OpenClaw is a multi-channel orchestrator.

You can ask questions in Telegram, run tasks from Discord, and use cron jobs to check email on a schedule—everything flows into the same coordinator and is queued and processed.

That’s why its architecture is much more complex.

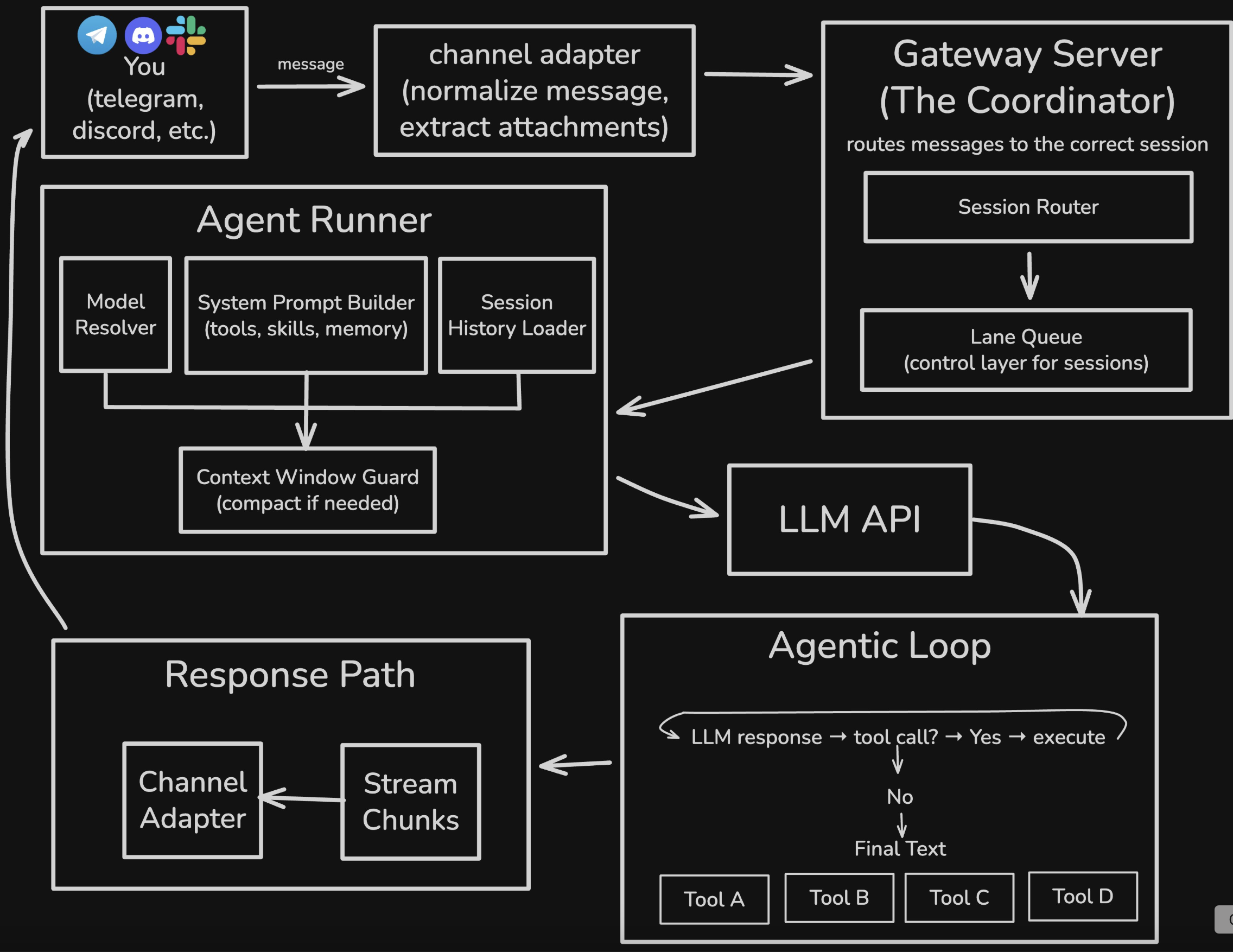

The six-layer architecture: the full path from message to response

When you send a message to OpenClaw on Telegram, it goes through these components:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

1. **You** — send a message via Telegram / Discord / WhatsApp

2. **Channel Adapter** — normalize message formats; unpack attachments

3. **Gateway Server** — session routing + lane queue orchestration

4. **Agent Runner** — assemble system prompt; load memory; check context window

5. **LLM API** — call the model (streaming supported)

6. **Agentic Loop** — tool-call loop until final text is produced

7. **Response Path** — stream response back; persist transcripts

8. **You** — receive the response

Next, let’s go layer by layer.

Channel Adapter: unify multiple channels

First layer: the Channel Adapter.

Each platform (Telegram, Discord, WhatsApp, Slack) has its own API shape, message structure, and attachment handling.

The adapter’s job:

- Receive raw messages

- Normalize formats into an internal structure

- Unpack attachments (images, files, voice)

So downstream components don’t care where the message came from.

Design principle: separation of concerns.

Each channel has its own adapter. If Telegram changes its API, only the Telegram adapter needs updates.

Gateway Server: the heart of task orchestration

Second layer: the Gateway Server—OpenClaw’s heart.

It does two things.

1. Session router

Route each message to the correct session.

What’s a session? A session is one “conversation context.”

- Your private chat with OpenClaw is one session

- A Discord channel is another session

- A WhatsApp group is another session

The session router uses the message origin to decide which session should receive the task.

2. Lane queue

This is the most crucial design.

OpenClaw uses a lane-based command queue to serialize operations.

Each session has a dedicated lane. Tasks within the same lane must execute strictly sequentially.

At the same time, low-risk and parallelizable tasks (e.g., cron jobs) can run on an independent parallel lane.

Why design it this way?

Because naive async/await parallelism creates race conditions.

Lane Queue: why serialization is the right default

This deserves a deeper explanation.

If you’ve built agents, you’ve seen this:

- The agent tries to read and write the same file concurrently

- Logs interleave and become impossible to debug

- Shared state behaves unpredictably under concurrency

The traditional solution is locks. But locks are easy to get wrong and mentally expensive—you’re constantly asking “do I need a lock here?”

OpenClaw flips the default: serialize by default, only parallelize when it’s explicitly safe.

This is aligned with Cognition (Devin’s company) in their “Don’t Build Multi-Agents” argument:

A simple async setup per agent will leave you with a dump of interleaved garbage.

Lane queues make serialization an architectural default rather than an after-the-fact patch.

The mental model changes from “What do I need to lock?” to “What can safely run in parallel?”

In most cases, the answer is “nothing.” Only truly independent tasks with no shared state belong in a parallel lane.

Agent Runner: dynamically assembling the system prompt

Third layer: the Agent Runner—this is where the AI truly enters.

It does four things.

1. Model resolver

Decide which model to use (Claude, GPT, local).

If the primary model fails (rate limit, service outage), it can automatically fall back to a backup model.

2. System prompt builder

Dynamically assemble the system prompt.

This is a key difference vs Claude Code.

Claude Code’s CLAUDE.md is statically injected—you write it once, it’s read as-is.

OpenClaw assembles prompts dynamically using:

- currently available tools

- installed skills

- memory read from

memory/ - the session’s context

That lets the agent “know” what it can do right now and what it remembers.

3. Session history loader

Load conversation history from .jsonl.

Each line is a JSON object recording: user messages, tool calls, tool outputs, and agent responses.

4. Context window guard

Monitor token usage.

If the session is approaching the context window limit, it triggers compaction—summarizing earlier turns to free space.

That’s why OpenClaw can sustain long sessions without blowing up.

Agentic Loop: the tool-calling loop

Fourth layer is the LLM API call plus the fifth layer, the Agentic Loop.

This is the standard ReAct (Reasoning + Acting) pattern:

- Call the LLM API (streaming supported)

- If the model returns a tool call → execute the tool → append results → go back to step 1

- If the model returns final text → stop

Default max loop count is ~20 to avoid infinite loops.

Why ReAct instead of Plan & Execute?

| Item | ReAct (what OpenClaw uses) | Plan & Execute |

|---|---|---|

| Execution flow | Step-by-step; decide next action as you go | Produce a full plan first, then execute |

| Flexibility | High (adjust to tool outputs in real time) | Lower (plan locks you in) |

| Token cost | Higher (each step needs full context) | Lower (think once in planning stage) |

| Best for | Exploratory tasks; unknown number of steps | Clear workflows; predictable steps |

ReAct is a reasonable choice: OpenClaw’s task space is too broad (from sending calendar invites to video editing) to pre-plan reliably.

ReAct’s core loop is: think → act → observe → think again.

This includes:

- Computer Use (shell commands)

- file reads/writes

- browser operations

- external API calls

Response Path: back to you

Sixth layer: the Response Path.

Responses are streamed in chunks (so you see the agent “typing” live), then sent back through the channel adapter to your platform.

At the same time, the entire session is persisted to a .jsonl transcript.

That transcript is part of OpenClaw’s “memory”: next time, the session history loader reads it so the agent can remember what happened.

Memory system: simple, but effective

OpenClaw’s memory system is surprisingly simple.

1. Session transcripts (.jsonl)

Full conversation transcripts per session, one JSON object per line.

2. Memory files (Markdown)

Long-term memory lives in MEMORY.md or inside the memory/ folder.

The agent writes to these files itself—no special memory API, just standard file-write tools.

3. Hybrid search

Search uses a vector search + keyword match hybrid:

- vector search (semantic): searching “authentication bug” can match “auth issues”

- keyword search: exact match for “authentication bug”

Under the hood: SQLite + FTS5 (SQLite’s full-text search extension).

4. Smart syncing

A file watcher detects memory file changes and automatically triggers syncing.

Notably, there’s no fancy compression, no forgetting curve.

Old and new memories have equal weight. Simple and explainable, but it also means memory files can grow without bound.

Computer Use: why not screenshots?

OpenClaw gives the agent full computer-control capabilities, including:

1. Exec tool (shell commands)

It can run in three environments:

- Sandbox (default): inside a Docker container

- Host: directly on your machine

- Remote: on a remote device

2. Filesystem tools

Standard read, write, edit tools.

3. Process management

Start background processes, stop them, and monitor status.

4. Browser tool

This is the most interesting.

OpenClaw’s browser mode doesn’t use screenshots—it uses semantic snapshots.

A semantic snapshot converts the page’s accessibility tree (ARIA) into text:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

- button "Sign In" [ref=1]

- textbox "Email" [ref=2]

- textbox "Password" [ref=3]

- link "Forgot password?" [ref=4]

- heading "Welcome back"

- list

- listitem "Dashboard"

- listitem "Settings"

Benefits:

| Item | Screenshot | Semantic snapshot |

|---|---|---|

| Size | ~5 MB | ~50 KB |

| Token cost | Very high (image tokens) | Low (text) |

| Interaction precision | Fuzzy (coordinate guessing) | Precise (use ref directly) |

| Speed | Slow | Fast |

Browsing is fundamentally a semantic task, not a visual task.

The agent doesn’t need to “see” what the sign-in button looks like. It just needs to know “there is a button named ‘Sign In’, ref=1.”

Security design: allowlists and dangerous-command blocking

OpenClaw’s security design is similar to Claude Code’s.

1. Command allowlist

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

// ~/.clawdbot/exec-approvals.json

{

"agents": {

"main": {

"allowlist": [

{ "pattern": "/usr/bin/npm", "lastUsedAt": 1706644800 },

{ "pattern": "/opt/homebrew/bin/git", "lastUsedAt": 1706644900 }

]

}

}

}

Users can allow once, allow always, or deny.

2. Safe commands pre-approved

Safe commands are pre-approved: jq, grep, cut, sort, uniq, head, tail, tr, wc.

3. Dangerous constructs blocked

Dangerous shell constructs are blocked:

1

2

3

4

5

# These will be rejected:

npm install $(cat /etc/passwd) # command substitution

cat file > /etc/hosts # redirection

rm -rf / || echo "failed" # chained with ||

(sudo rm -rf /) # subshell

Core principle: maximize user autonomy while blocking obviously malicious operations.

Frankly

Strengths

- Multi-channel support: one agent across Telegram/Discord/WhatsApp/Slack

- Serialization by design: lane queues eliminate most race conditions

- Dynamic context: system prompts are assembled based on current state

- Persistent memory: simple but effective Markdown + JSONL

- Semantic browser snapshots: ~100× cheaper than screenshots

Weaknesses

- TypeScript constraints: smaller ecosystem than Python; harder ML-tool integration

- Serialization bottleneck: no parallel tasks within one session; long tasks block

- Memory bloat: no forgetting;

memory/keeps growing - Security risk: giving an agent computer control is inherently high risk

The fundamental difference vs Claude Code

| Item | Claude Code | OpenClaw |

|---|---|---|

| Interface | Single terminal entry point | Multi-channel (Telegram/Discord/etc.) |

| Execution mode | User-triggered | User-triggered + cron jobs |

| System prompt | Static (CLAUDE.md) | Dynamically assembled |

| Memory | Single-session | Cross-session persistence |

| Browser | None | Semantic snapshots |

Claude Code is a tool. OpenClaw is an employee.

A tool moves only when you use it. An employee checks email, remembers what you assigned yesterday, and proactively reports progress.

That’s why OpenClaw’s architecture is so much more complex—because the usage scenarios it supports are more complex.

FAQ

Q: What language is OpenClaw written in?

TypeScript. Not Python, not Next.js, not a web app. It’s a local CLI that exposes a gateway server for multi-channel messaging.

Q: How is a lane queue different from typical async/await?

With typical async/await, concurrency is the default and you add locks to avoid race conditions. With lane queues, serialization is the default and you explicitly mark what can run in parallel. The mental burden shifts from “what do I lock?” to “what can safely run in parallel?”—and usually the answer is “nothing.”

Q: Why use semantic snapshots instead of screenshots for the browser?

Because screenshots are ~5MB and semantic snapshots ~50KB—about 100× cheaper in tokens. And browsing is a semantic task: the agent doesn’t need pixels, it needs named UI elements like “button ‘Sign In’.”

Q: Will OpenClaw’s memory slow down over time?

Yes. Without a forgetting mechanism, files in memory/ grow indefinitely. Weekly maintenance helps: keep daily notes for the last 7 days and move important info into MEMORY.md.

Q: How do you handle security risks?

OpenClaw provides allowlists, pre-approved safe commands, and blocking of dangerous shell constructs. But the real issue remains: giving an agent computer control is inherently risky. Run it in an isolated VM; don’t run it on your primary machine.

Further reading

- OpenClaw Memory System, Fully Explained: SOUL.md, AGENTS.md, and the Painful Token Bill — deep dive into the memory architecture

- OpenClaw four-layer defense-in-depth hardening guide — must-read security setup

- From “wrapper 1.0” to “wrapper 2.0”: why Anthropic should be the one sweating — ecosystem perspective

- Personal AI Assistant Showdown Week: Claude Code vs OpenClaw — different paths, same destination — comparing the two routes

- I used OpenClaw intensely these days: why I decided to include it in my workflow — hands-on experience

About the author:

Wisely Chen, Head of R&D at NeuroBrain Dynamics Inc., with 20+ years in IT. Former Google Cloud consultant, VP of Data & AI at Yunglien Logistics, and Chief Data Officer at iCharging. Focused on practical enterprise AI transformation and real-world agent adoption.

Links:

- Blog: https://ai-coding.wiselychen.com

- LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/wisely-chen-38033a5b/